Eric Distad had been posting instant film photos from his treks through abandoned places on social media. But he started to hold back a few of the square Polaroid photographs, and arrange them instead on a table or the floor.

He knew they were telling a story, even though he didn’t have words for it at the time. It started with a few photos, and then more as the fictional tale took shape in his mind. Finally, he arranged 72 images into nine chapters. Only then did Distad begin to write that story through captions.

Photographs from that project, “A Garden Not Lost to Us,” are on display in Distad’s show, “Taking Shape,” which opens Jan. 30 at Scarlow’s Gallery. A limited number of “A Garden Not Lost to Us” books also will be available for sale the day of the opening.

“It’s a fictional journey but it has a lot to do with loss, the development of insight and transformation,” Distad said. “There are some mythological elements the narrator encounters on his journey, and those reflect the process of his transformation.”

His passion for abandoned places began by chance. He took his SX-70 instant film camera on a hike through the woods near his home in Maryland in 2007, though he wasn’t expecting to find anything to photograph. But he came across an abandoned agricultural structure, sneaked in and photographed it.

Then he met his friend and fellow photographer Brian Henry through an online photography community, who served as a guide into scores of abandoned sites including schools, factories and hospitals, Distad said. He also influenced Distad’s direction into photographing exclusively with instant film.

Distad met the woman he’d marry, Laura, through photography as well. She soon joined their outings and became the subject of some of the photos that appear in the exhibition. She also designed the book they published in time for the show opening.

The only tweaks Distad made to his prints were to digitally remove dust spots and match the color exactly to the originals, he said. After all, it’s the unpredictable colors and effects he most enjoys about the retro medium, which has been making a comeback in recent years, he said.

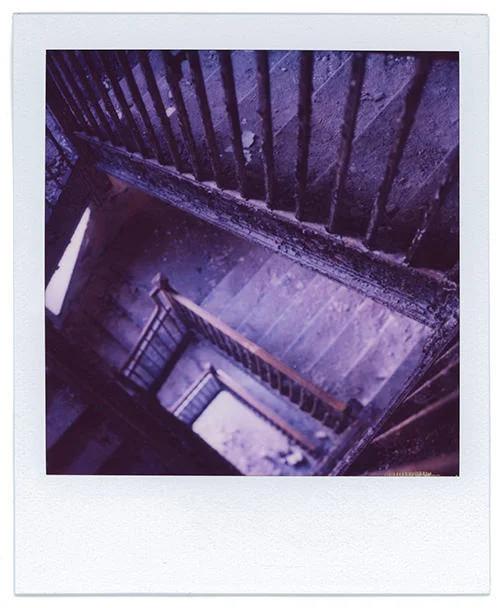

In one shot featuring Laura, for instance, the cold evening that made her shiver also spread deep purple tones as the image developed. Long-expired film developed into fiery shades in other photos. Slightly dirty film rollers also added colored, spherical patterns across some of the images.

“I have so much of a love for the unexpected that comes with instant film developing, based on the age of the film, the temperature that day and the light—you can get effects you’d never expect,” he said.

Instant film also adds the challenge of having to compose on the spot to keep the original white border instead of cropping later.

Exploring abandoned places always is an adventure filled with discovery, Distad said.

“They’re always going through this period of decay,” he said. “You’re never sure what you’re going to find when you go there. Some things have collapsed and they provide new places where you can walk and new rooms that you can see that weren’t available to you before. Sometimes there are visitors, be they owls swooping down the roof of a barn to dive bomb us or whether they are people you don’t know who are going through these buildings who we’re afraid of who we’re to run into.”

Distad’s photography is influenced by psychogeography, which examines the way geographical environments influence on the emotions and the behavior of the people who move through them, he said. The field emerged as an artistic movement in the mid-1950s mainly in Paris, though some have argued that some of its features date to 1800s literature, he said.

“But for my writing, it had to do with writing about abandoned spaces,” Distad said. “Those abandoned spaces are on the border between man’s fading influence and the return of nature.”

A 28-page paper he wrote last summer and posted on his website delves into his own, new approach on psychogeography- along with his other influences, especially the Russian novel “Roadside Picnic” by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky and a Russian art film called “Stalker” directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, he said.

The Casper native has enjoyed taking photos from the time he received his first camera at about age 6, and he studied photography in 4-H, he said. He later earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology from University of Wyoming and his master’s degree in criminology at University of Cambridge. He returned five years ago to Casper, where he’s the data specialist for Wyoming Child and Family Development, which administers Head Start and Early Head Start programs, he said.

Instant film reignited his interest in photography after it had fallen by the wayside in his teens. He’s been shooting since. Distad continues to explore places through photography, including a series on Wyoming landscapes yet to be shown, he said.

“The properties of instant film make it the ideal photographic medium for exploration,” he said in his artist statement. “As a vehicle for an unfolding narrative, instant film photographs are raw, mysterious, and unpredictable. No other form of photography so effectively pulls the artist into the process of illumination and discovery and makes him or her so directly a part of the story.”

Besides photographs, visitors of the exhibition will see objects that appear in some of the photographs on display in the gallery window, along with the camera Distad used to create them. A film projection also lets visitors see a Polaroid developing.

Scarlow’s gallery owner, Claire Marlow, grew more intrigued by Distad’s images and the depth beneath his art as they collaborated for the exhibition, she said.

“It was about thought process and asking people to think beyond the typical boundaries of art and even photography,” Marlow said. “I am very excited for the gallery to be able to offer a show more focused on concept and installation and walking through an experience, to really step out of our typical gallery role.”

Follow reporter Elysia Conner on Twitter @ink_pix